Does low tax generate growth amidst inequality?

By Rohith Muthuvelu

“Taxation is the price which civilized communities pay for the opportunity of remaining civilized”

-Albert Bushnell Hart

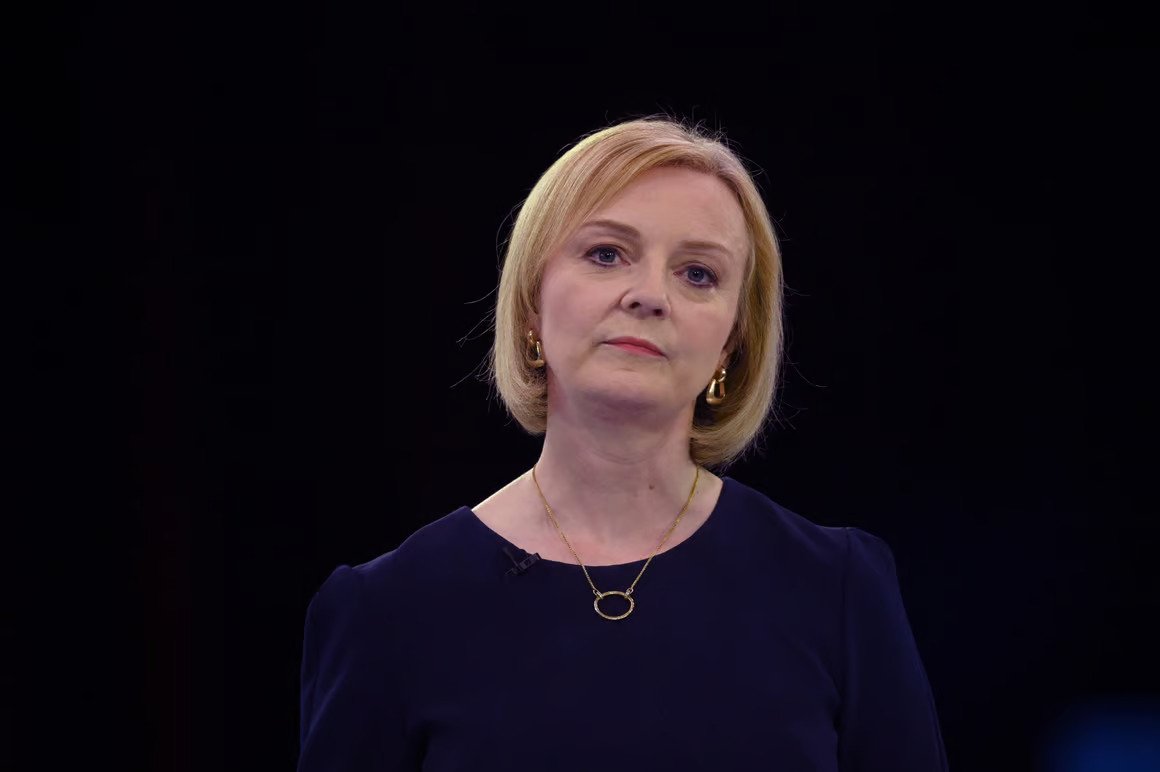

“The government under Liz Truss proposed ‘trickle-down economics’ framework. Discuss its implications on ‘levelling up’, in light of the high territorial inequality in the UK.”

The dilemma of ‘trickle-down economics,’ and the potential success of its implementation to ‘level up’ is interesting, if truly answerable; for it incorporates determinants from several faculties. Notably economic, social and psychological, it also scrutinises the very political fibres which bind the array of Tory factions together. Given the unambiguous ‘territorial inequality’ present within the United Kingdom (UK), if I conclude that the ramifications of such a ‘macroeconomic framework’ are altogether negative, I shall have exposed the axiomatic falsehoods of traditional conservatist ideals, due to their inevitable neglect of major, domestic communities.

In order to correctly answer this question, one must first define integral terms. Within this essay, ‘levelling up’ refers to “the (Conservative) political policy which aims to mitigate economic, moral, and environmental, imbalances between geographical areas and social groups in the UK, via the improvement of the underprivileged, therefore not to the detriment of the privileged.” First coined in 1868, it refers to a positive means to equality, whereby the “uncomfortable” are bettered, as opposed to the “comfortable” being worsened. This therefore ought to improve ‘territorial inequality’ and median standard of living, the latter being a universal objective of government. ‘Trickle-down economics’ refers to “economic policies which disproportionately favour the upper end of the economic spectrum, indirectly benefitting those earning lower incomes.” That includes high-income earners, firms, banks, and their capital gains and dividends. Logically extrapolated, this concept follows the belief that economic indicators are disproportionately dependent upon such agents, which drive investment, growth, and expansion. Resultantly, the bonuses of which should “trickle down” to the lower classes, for instance in the form of lower unemployment and greater human capital. The instantaneous fall in tax revenue is theoretically replaced by increasing Long-Run Aggregate Supply, leading to workers’ eventual potential for higher taxation, and therefore net growth. One can assume this is affiliated with traditional Conservative ideals (greater numerical equality in tax rates between classes). Finally, ‘territorial inequality’ reflects “the imbalance in welfare between geographical locations.” Rimisp’s “International Conference on Territorial Inequality and Development” concluded that this is caused by economic agglomeration of different classes, leading to the formation of multiple “spatial equilibria” dependent upon wealth (agents are often geographically grouped together by affluence). Therefore, overall inequality is inextricably linked to ‘territorial inequality,’ as economic echelons are correlated to localities. Characterised by varying political, educational and health opportunities, such is exhibited by Westminster’s average Male Life Expectancy of 84.9 years, in comparison to Glasgow’s of 73.6 years (13.3% less); inferably, civilians’ rights are violated chiefly due to circumstances beyond their control, requiring intervention.

I will eventually conclude that ‘trickle-down economics’ theoretically mitigates inequality, although the non-uniform nature of human-behaviour and lack of ‘spatial’ addressment, deem financial liberalism of high-earners unsuitable as a solitary means to equal growth. If successful, ‘trickle-down’ economics supplements ‘levelling up,’ even providing government revenue to fund it; therefore, in this essay, its effects must be viewed as assisting ‘levelling up,’ purely for the objective: ‘equality’.

Firstly, many traditional Conservatives believe ‘territorial inequality’ can be mitigated by the liberalisation of high-worth economic agents, as their rise in Investment derives the need for more total workers, reducing pre-existing economic disparity. Evidently, Liz Truss believed so, planning to abolish the 45% tax rate for individuals’ earnings exceeding £150,000. This therefore would have proportionately enhanced this category’s investment, with a constant insatiable, capitalist desire for wealth, and greater disposable income to obtain it; Aggregate Demand would theoretically rise. Exemplified by Bush’s EGTRRA, a high-income tax cut from 39.6% to 35% swiftly led to the end of the 2001 recession; and so, with greater spending, and greater access to credit from financial institutions (also high-worth bodies) to further facilitate it, many suppliers would raise prices, and receive increased revenue. This fractional increase could therefore be distributed to workers, thus ameliorating their wages, proportional to standard of life (when materialistically spent). On an Aggregate scale, this increases Long-Run Supply, as eventually more unemployed labourers will be hired, with revenue utilised to improve human capital. Thus, previously poorer workers are financially “bettered,” limiting their disparity with higher economic agents, tackling inequality. In terms of National Income, AD = GDP; therefore, ceteris paribus, GDP is inversely proportional to higher top-band taxation, and so where the latter falls, there ought to be greater resources (wages and services) available to previously lower-worth economic agents. Although, in order to mitigate ‘territorial inequality,’ one assumes a sufficient geographical distribution of national income, a problem observable with the arguable, systemic neglect of the North of England; this however, is independent of ‘trickle-down’ economic policy, but dependent upon leadership priority, and so is excluded from consideration. The aforesaid argument suggests that economic policy to boost total investment is advantageous, as it increases both Long-Run Aggregate Supply, and GDP, benefitting poorer workers. However, that relies upon improving average workers’ wages; whilst this may mitigate total inequality, production is likelier to transpire in regions with pre-existing infrastructure, as this permits an increase in short-term supply – therefore, territorially, this would exacerbate short-term inequality amongst labourers, and poorer workers from relatively neglected regions would be quite unimproved.

Also, the mere concept of investment driving equality entirely depends upon executives using tax cut revenue for expansion, employing workers, or increasing wages, a notion with stark absences of empirical consistency; limited progression to equality, let alone ‘territorial equality,’ is frequently made. For instance, Amazon, valued in 2021 at $1.6 trillion, incurred Coronavirus booms of $680 billion from its pre-pandemic worth of $920 billion (73.9% increase); despite allocating $75 billion directly to C.E.O Jeff Bezos, average warehouse employees’ wages stagnated to approximately an annual $31,000 – made by the leader every 12 seconds. This therefore proves that human executives cannot be relied upon to display uniform economic behaviour, and as ‘trickle-down’ policies distribute power toward them, its success depends upon their likelihood to counterintuitively allocate; hence, it often fails. Moreover, under the hypothetical assumption that tax-cuts do boost investment, Michal Kalecki supplements the evidence of Bezos, suggesting that capitalist income (Gross Profit) is caused by capitalist investment and consumption – therefore, capitalist investment is within a closed system, the profits of which, are only enjoyed by other capitalists:

Gross Profits = Gross Investment + Capitalist Consumption

In this sense, there exists no fathomable capacity for high-worth agent benefit to ‘trickle-down’ and mitigate ‘territorial inequality.’ Now, although this model considers a worker to be one with no savings, a far smaller proportion of the contemporary economy, it is perhaps evident in the case of China, whereby the Eastern Coast, responsible for almost all production, contains 90% of the provinces above the mean rural income. Yet, the holistic GINI coefficient is 0.466 (2021); therefore, the differing spatial “equilibria” are clearly present; and so, as such workers benefit from their proximity to production epicentres, and are “capitalists” under Kalecki’s model, their investment evidently heightens ‘territorial’ inequality, as their own province’s hoarding of China’s wealth is merely encouraged. The likely failure of ‘trickle-down economics’ is furthered, because even theoretically, marginal boosts in Aggregate Demand caused by greater capitalist investment are only productive, whereby the economy is not at full employment, or in coexistence with definitive supply side policies.

Figure 1: Shift of AD1 to AD2 where economy is nearing full employment

As observable in Figure 1, nearing full employment, a rise in Aggregate Demand causes a disproportionately small increase in Real Output, Y, and a disproportionately large increase in Price Level, P, leading to inflation. This transpired in Liz Truss’ attempt, as average prices rose to 10.1%, the highest in 40 years, annihilating consumer’s confidence to even invest. This links to how ‘trickle-down economics’ cannot lead to greater ‘territorial equality,’ as high-worth agents cannot be relied upon to display uniform investment in workers. Even in that unlikely event, spatial differences in wealth would be heightened, with the same class incurring much of the benefit in a closed-system.

However, of the assumption that maximised governmental tax revenue can boost growth, many republicans argue that whilst ‘trickle-down’ policies may heighten short-term ‘territorial inequality,’ their capacity to grow national revenue can eventually increase equality. According to Arthur Laffer, the tax cut effect upon government revenue occurs in a curve, the “Laffer Curve,” whereby in a “prohibitive range,” the eventual boost to growth of a tax cut outweighs the immediate, “arithmetic” loss. Hence, a stronger base for expenditure is formed:

Figure 2: "Laffer Curve" - Government Revenue plotted against Tax Rate

Whereby taxation rates are currently above optimum, t*, a reduction causes a rise in Government Revenue. This region, t > t*, is the “prohibitive range.” For instance, in response to crippling “stagflation,” President Reagan reduced the maximum rate of taxation from 70% to 28%, a fall linked to the ending of the 1980 recession, highlighting the importance of ‘trickle-down’ policy in growth. However, it transpired simultaneously with a 2.5% increase in government expenditure, potentially the truthful origin of improvement. This therefore proves that any likely success of such framework must coexist with governmental spending, with the two possibly being causally linked – greater potential for government revenue permits greater government expenditure, originating from ‘trickle-down’ theory. Furthermore, according to studies conducted in South Korea, “lagging territories” can be improved by emphasis upon “endogenous growth,” with a “regional specialisation;” ‘territorial inequality’ is solved by “place-based development policies.” Demonstrated in the case of ‘levelling up,’ greater tax revenue can be used to institute planned “skills training,” to generate a long-term source of economic dependence. This is idiosyncratically applicable to underprivileged workers. Therefore, as “Rimsip” suggests they are concentrated in such underprivileged territories, greater emphasis upon them directly combats the issue of ‘territorial inequality, as these regional workers are permitted to earn in abundance from higher-skilled labour. Moreover, much of the counter-argument relies upon the assumption that executives lack the psychological uniformity to invariably expand and improve wages; however, this is immaterial with the introduction of greater minimum wage legislation, coercing firms to follow ‘trickle-down’ policy. This is proven, as research conducted in Canada in the 1990s concluded that wage dispersion is reduced by higher minimum wages.

Therefore, as communities are often dictated by wealth (territorial equilibria by affluence theory), it follows that polarised ends of such wealth dispersion are from certain territories – hence, mitigating wage dispersion is proportional to mitigating territorial inequality. This suggests that ‘trickle-down economics’ in accordance with the Laffer Curve increases government tax revenue, reducing ‘territorial inequality’ via investment into endogenous growth and minimum wage legislation. However, evidently, the curve’s optimal tax rate (for equality) exceeds what is frequently in place, and so in practice, cuts such as Truss’ only reduce government revenue, leaving negative funding to potentially alleviate inequality. Also, raising minimum wages lacks purpose in sectors whereby median pay already exceeds it, and so demand for labour at the lowest legal wage would simply contract, increasing low-worth agent unemployment, thus fundamentally exacerbating ‘territorial inequality.’

Furthermore, contemporary economists suggest that high-income individuals are proportionately less likely to invest, as the care to expand personal income exponentially declines with income itself. According to Kahneman’s Princeton thesis (2010), happiness of agents rises proportionately more with income, as “basic needs” are being met. However, once exceeded, the fulfilment acquired from pecuniary success diminishes, and so eventually, there is a general reduction in desire to expand one’s fortune. Therefore, the rise in Aggregate Demand due to high-worth agent tax cuts is often limited, thus providing minimal resources to ‘trickle-down’ to the underprivileged; rather counterproductively, (territorial) inequality is heightened, as logically the revenue of the wealthy is bettered by a multiplier greater than that of the poor being “bettered.” As proven by a study of 18 countries conducted by David Hope and Julian Limberg, the effect of reducing top-band taxation upon the underprivileged is intensely finite. Over few decades, the wealth of top 1% earners even tripled, with almost no alteration to long-term unemployment and real GDP per capita – in fact, short-term unemployment rose by up to 6%, as firms scrambled to mobilise resources (however this can be ignored as it was theoretically a means to a positive end). Yet indisputably, income inequality grew, as high-worth agents benefitted proportionately more than their counterparts, with less than proportionate mitigation by investment. Furthermore, investment itself is dependent upon many external variables, not limited to pre-existing wealth. We can unequivocally observe that animal spirits, most notably confidence, majorly drive investment patterns into cycles, as our psychological capacity to invest is correlated to the changeable herd; according to Kahneman, “high cognitive ease” is associated with decisions made by others, with “confidence” being of the Latin “fidere,” meaning “to trust.” Therefore, particularly whereby confidence is (irrationally) low, investment is limited beyond our power; therefore, it is impossible for human agents to always uniformly act, in this case to benefit others. Ultimately, as ‘territorial inequality’ is mostly limited by governmental investment, or capitalist investment. Whereby the latter is theoretically varied by both pre-existing wealth and animal spirits, it theoretically varies also – therefore, less is available to ‘trickle-down’ to low-worth agents, which, when reinforced by potent empirical evidence, deems the intrinsic capacity of Truss’ ideals to be critically limited.

Figure 3: Demonstrates cycles in investment and GDP, caused by cycles in confidence

Figure 3 illustrates the unpredictable variation of investment, highlighting the falsehood of policy which depends upon it.

Overall, the concept of ‘trickle-down’ economics is evidently not one to be vaguely oversimplified, with the need for empirical and mathematical scrutinization being increasingly clear. Nevertheless, I believe that such policy would fail to mitigate ‘territorial inequality.’ Thus, it would not assist ‘levelling up,’ which, in coexistence with ‘trickle-down’ theory, would constitute a gargantuan misallocation of public resources, as government revenue may even fall.

Ultimately, this dilemma can be summarised by the compatibility of economic conjecture, and the external variables of ignored significance, dictating practical truth. In order for ‘trickle-down’ policies to theoretically succeed, high-worth agents must categorically invest, aggregate demand must extend aggregate supply, and capitalists must spend profits on increasing the lower classes’ value. Yet, each stage in this consequential succession depends on several other variables, which invariably do not align in optimum. For instance, although following the “Laffer Curve” should maximise government revenue, this is contingent upon an exponentially declining desire to invest – and that is simply the inadequacy of ‘trickle-down’ policy alone; in the context of ‘territorial inequality,’ as increased investment possesses no correlation to researched solutions themselves: localised kick-starts and long-term sources of labour (endogenous growth), it lacks theoretical coherence, even causing Piketty’s “extreme level of wealth inequality” as only pre-existing industry is encouraged. In conclusion, policy reliant upon non-uniform human behaviour in practice displays uniform unsuccess; their dependence upon other factors (such as lifeline government spending) to succeed deem them not to be individually self-sufficient. Hence, with exclusive regard to ‘territorial inequality,’ ‘trickle down’ policy is not sustainable, and therefore the Conservative factions pursuing both desirable ends fail to observe their evident incompatibility.